Being a war generation ourselves, we have our part of traumas. The traumas of Artsakh (Karabakh) war are always in a corner of our memory and sometimes remind us about themselves. The intention of exploring trauma took us to Serbia – Belgrade, where we were trying to understand if the trauma was overcome after twenty years of the Serbian conflict.

Our aim was not turning to the war at all. Having our own Artsakh war memories we know what that is. We have tried to look beyond the borders and boundaries in the project, to explore someone else’s pain or the pain known to us from someone else’s perspective. Neither to represent the war, the unresolved conflict, nor to judge the right or wrong sides, but to see the consequences and impact of it on people, cities, and younger generations.

The project includes three narratives, each of which uniquely discovers the relations of time and traumas.

While people — actual witnesses — and the bombarded buildings in the city center silently carry the traces of time, the younger generation tries to look ahead. The three narratives together try to create the psychological portrait of what we saw and heard in Belgrade after twenty years.

Our aim was not turning to the war at all. Having our own Artsakh war memories we know what that is. We have tried to look beyond the borders and boundaries in the project, to explore someone else’s pain or the pain known to us from someone else’s perspective. Neither to represent the war, the unresolved conflict, nor to judge the right or wrong sides, but to see the consequences and impact of it on people, cities, and younger generations.

The project includes three narratives, each of which uniquely discovers the relations of time and traumas.

While people — actual witnesses — and the bombarded buildings in the city center silently carry the traces of time, the younger generation tries to look ahead. The three narratives together try to create the psychological portrait of what we saw and heard in Belgrade after twenty years.

Historical overview

This conflict, arisen from the collapse of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, began in 1992 and continued up to 1995

SURVIVOR’S

TRAUMA:

These people having passed through the war have fled leaving behind all they had created, their houses, their familiar environment. Many of them have lost not only their material belongings, but also their mental calmness and health. Many of these people that live now in Belgrade, have not yet regained peace and normal conditions to begin their life again. They continue to be in conflict with their past and suffer their traumas once again after recalling it.

“There is one pain and it will remain forever, it cannot be cured or wiped away. There can be no greater trauma than when you see that your wife is falling and her arm is blown out. We tore a curtain and some dress to tie her hand. The bomb shrapnel hit her. I am a man, it would be easier for me to endure such pain. When I saw that her arm was blown, I first thought that they would have to cut it off. If they do that, what will she do then? We’ll carry it with us while we’re alive. No one can heal this, and we don’t even ask for someone to heal these wounds because they are ours”. Milan Radisevic

“I now have a new home and I am happy. I am satisfied. I at least know that this is mine. I had an apartment and a big house in Sisak. I was left without anything. We couldn’t sell it and use the money to buy something in Serbia. We got this and feel grateful, one must be humble”. Nevenka Radisevic, 69

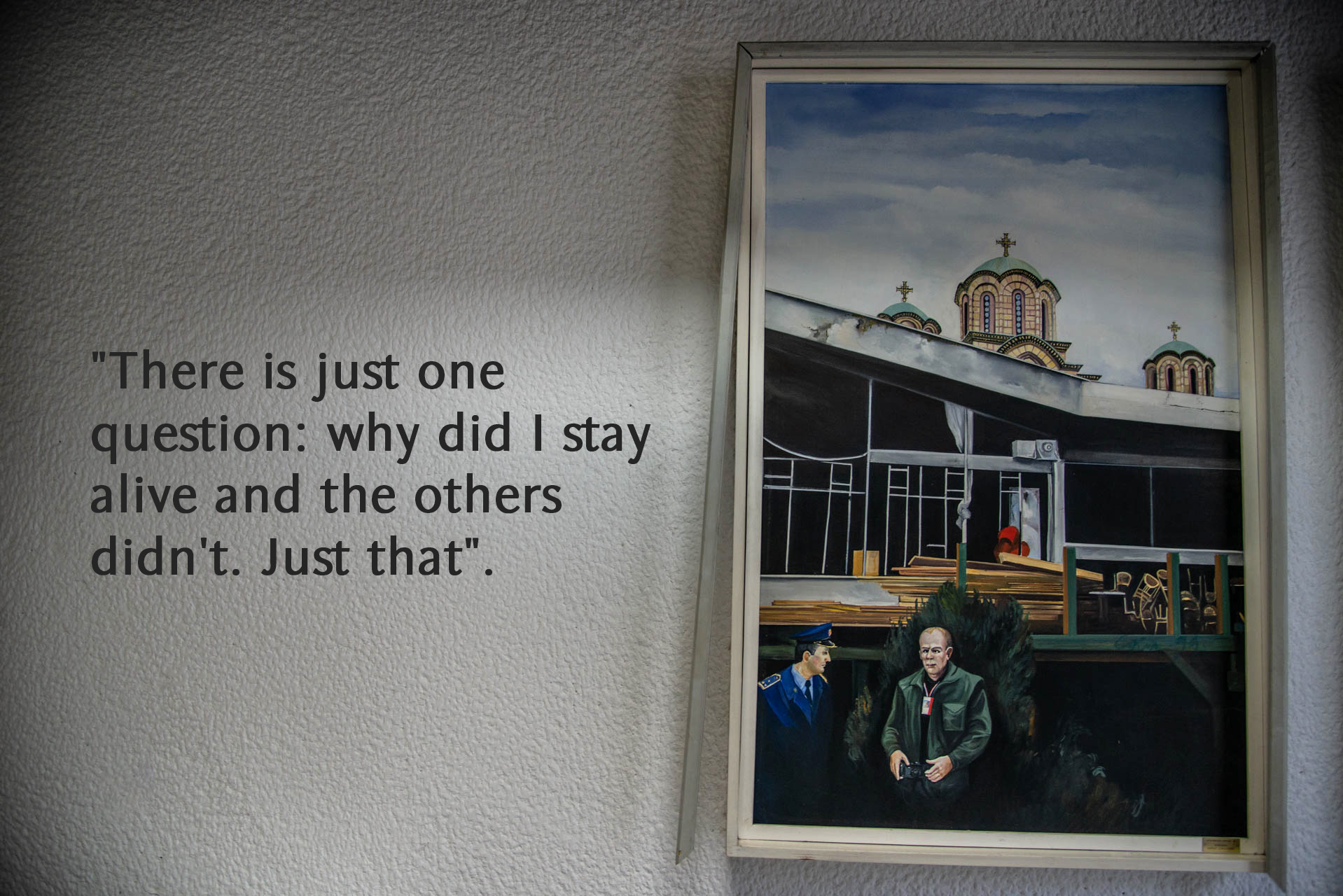

CITY’S TRAUMA:

People’s destroyment of the environment created by other people has a memory too. The bombarded building of the Serbian State Television is standing in Belgrade till now, which has a national value and is one of the bombarded buildings. This building carrying all the heavy traces of the war over it is an example of trauma and a unique memorial reminding about the circumstances of it.

“When I explain to people, I can’t picture what it looked like. It was like there was a huge excavator at a distance of 1 cm in front of you. There was no sound. Terrible silence at that second. You feel pushed by some force and unable to defend yourself. Suddenly – a total darkness. Two meters from me, I saw a light that had not gone out. But for the next five minutes, I couldn’t get to that light, because there was much dust, my throat was scratching from the dust and rocket fumes. The first thing was shock. I didn’t know whether I was alive or not.” Dragan Tosich, 48

YOUNGSTERS’ TRAUMA:

More than twenty years have passed from the war. The younger generation is not the immediate sufferer of war memories. Their parents, grandfathers and grandmothers have formed their conceptions and memories by their stories, by passing their own traumas. The youngsters have learned about the past also from media, school, and street. For sure, the city scape also has its impact on them by its bombarded buildings. What do youngsters think about what has happened and about the future? Do they live by it or do they try to build the future? Or, on the contrary, do they want to destroy the bond between the past and the future?

“I do not have hatred for these people, because I cannot blame the whole nation for something that was the decision of specific politicians and concrete people at that time. I have an equal attitude to all nations. But I cannot say that there is no hatred in our nation։ That hatred is caused by a difficult period and because it is difficult to distinguish between what is a nation, what is a state, and what are individuals. That’s why I don’t blame people who feel hatred. They don’t want to go to America, they don’t like the West in general. I think that future generations should not be educated in this spirit. We should distinguish between politicians and who is to blame”. Katarina Drobnjakovic, 23

Photos, videos, and interviews by Nazik Armenakyan and Piruza Khalapyan

Translation by Diana Milosevic and Anna Davtyan

Text editing by Anna Davtyan

Web design by Karine Ghadyan

The project was prepared in the framework of “Strengthening Independent Media in Europe and Eurasia” project implemented by Media Initiatives Center, with the financial support of Internews.