There is no beginning to this story. I didn’t photograph. I didn’t write. It was hard. It’s hard for me now, too, when I re-feel it. It was even harder on the morning of April 21 when we sent her off to “Saint Gregory the Illuminator” Medical Center. COVID-19. Infection. Death. Fear. Waiting. Uncertainty… The house felt empty without her.

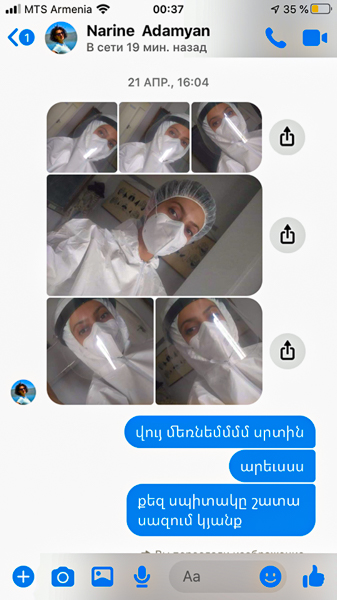

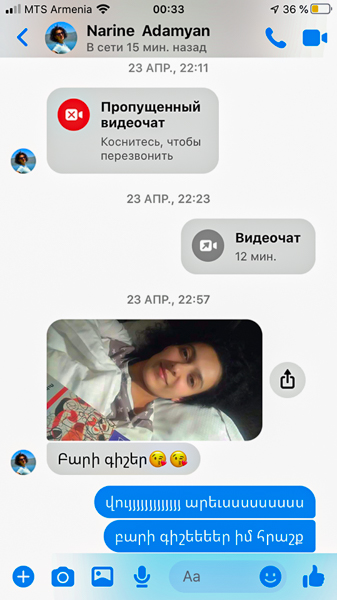

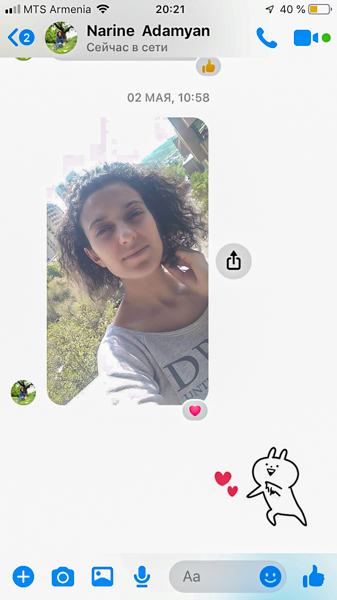

Dad is always scared when one of us isn’t at home, when the house gets empty. This time we were all scared. We were scared when Narine was calling, and we were even more scared when she was not calling. We only knew that we had to wait, and she will call when she has time, or when she isn’t asleep. We were waiting, counting the living, the dead, and then the recovered. We lost and found ourselves amidst her calls.

I photograph Narine near the hospital, I feel her anxiety and tension. Everything is as uncertain as in spring. Only now it is summer. After the vacation, Narine goes to the hospital again, where she has been working for about 15 years, first in resuscitation, now as an X-ray nurse.

Now, a few months later, as I try to recreate the chronicle of those days, I want the photos to tell not about COVID but about life, about love, about hope, about the human. But also to tell about the invisible side of the epidemic through a person, through his emotional experience. In this case my sister was the transmitter according to whom human feelings behind the epidemic remained veiled.

When Narine came home on June 21, everything was the same and not the same. It seemed that we knew everything, that she told us everything – about when she woke up, when she went to bed, what she ate, where she spent the night, how many times a day she disinfected her hands, how many patients she had, how many times she measured their and her body temperature. But that was what was visible from the outside. We knew little about the inside. The only thing we knew was that it’s a short break during which she wants to recover. I decided to photograph that very transition, the process of recovery, the change, because at home Narine was already silent, just like a soldier who came home from the army, who is being cherished, fed and isn’t asked unnecessary questions.

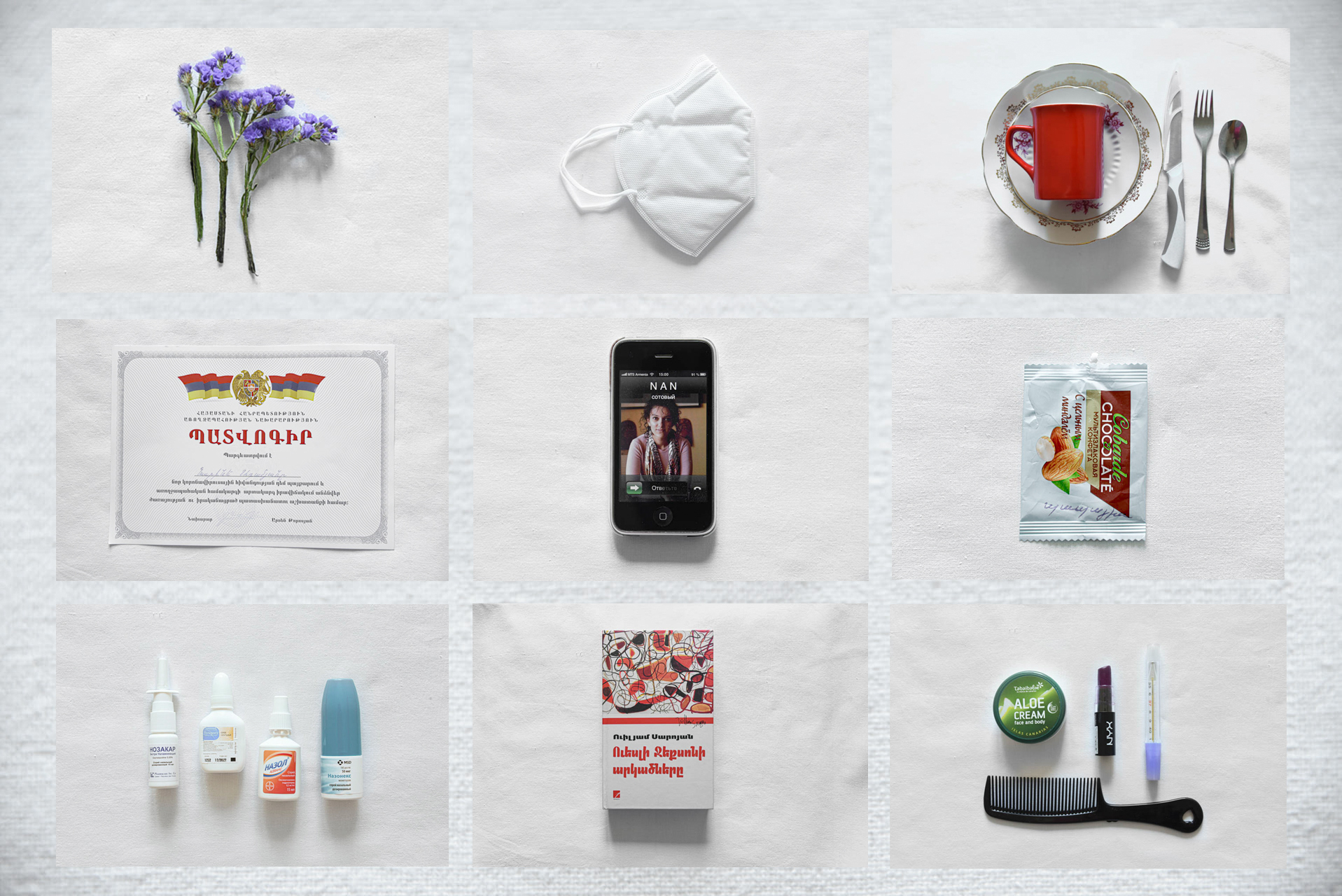

Everything has its story. The first thing Narine put in her suitcase was “The Adventures of Wesley Jackson” by Saroyan։ Saroyan kept her alive during that time. When Narine’s call avatar image disappeared from the phone my mom was restless for several hours. For her it was as if Narine disappeared off the face of the earth. One day my sister sent us letters on candy wrappers. Me and my mom ate the candies and threw the “letters” away. Dad kissed them and promised to keep his daughter’s letters. A few months later I found the papers in a notebook, it turned out it was not a joke…

Narine spent the last two days of her isolation at home and immediately set her dishes aside on a corner of the table. Although both of her test results were negative she lost her sense of smell for a long time, and it turned out that her airways were damaged, and the doctor prescribed different drugs.

I wanted to photograph Narine without heroizing her, just as she is – strong in her decisions, fragile in her emotions, striving for the maximum, but also satisfied with a little. I wanted the pictures not just to show a beautiful girl but someone who has a character and a strong sense of responsibility.

I became a photographer for my sister, and although the roles were clear, it took time to adapt, to accept, not to notice the camera, and also to talk. Sometimes she got excited during the recordings, took long breaks. We were more than sisters then.

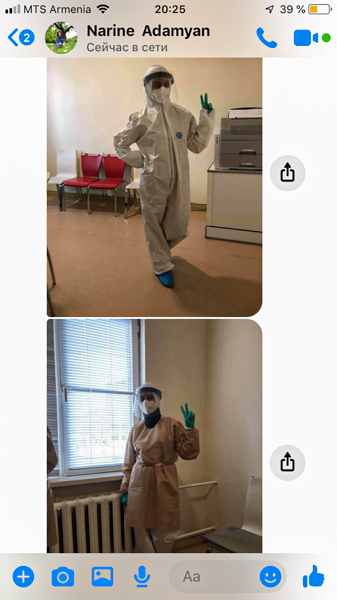

At the hospital, we all seemed to be in the same boat where it was impossible without mutual support. You are constantly in touch, the walkie-talkie is on, because every minute a new stream of patients is coming. A state of high mobilization, where your quick response is important. You become a link in the chain, which in case of getting infected leads to inevitable chain reaction. It is here that you realize the extent of your personal responsibility.

During the communication with the patients I tried to inspire them in every way, to say, for example, that they are already in good condition, and that they look recovered. No one was ready to spend that much time in the hospital, and no one expected that the course of the disease can be so severe. They kept asking when they were going to be discharged from hospital and go home. There were even people who simply could not speak because every breath was possible with the help of a breathing machine.

Narine takes care of her feet: sleepless and long nights in the hospital hit the feet first. Swelling, lumps, broken capillaries – all medical workers “inherit” them over the years.

But there was an impression that we live in parallel realities: people who lived a normal life, and us, whose normal lives were disrupted. A feeling that life is passing by you, the time is slowing down. If I was to title the period following that time, I would say hurry to live, because afterwards you try to make up for everything you missed during that time. And during that time the emotions, feelings, sensations, experiences, the feeling of enjoying life were missing the most.

Narine doesn’t wear much make-up but she likes to take care of her face, it’s a small ritual before every meeting.

On the evening of August 1, before her shift, Narine irons her medical uniform and tries to tune in for tomorrow.

When I decided to take a break from work, I joked that all my meetings were left behind. I wanted all this to end soon so that I could go to meetings, meet new people, create new relationships, new acquaintances. It seemed that all of this fell back. Maybe if everything went normally I won’t have such a demand. Restriction sharpens the perception of freedom. What was usual becomes desirable one day: just to wake up and have a cup of coffee with your loved ones in the morning. Sometimes very simple things were missing, such as the taste and smell of your favorite food, but in general, human communication was missing.

I dreamed that all this would end soon, and I would get back into my normal rhythm as soon as possible, when I could just go out and walk.

This phase made me learn about flexibility because life is not static. One day we all woke up and realized that life was no longer the same as before. It was a challenge for everyone to see how stress-resistant, flexible, resourceful and willing to change they are. The reality we imagine can change in one day, and you must have the resources to adapt and live in change.

Early morning of August 2: Narine is on duty at the hospital again after the vacation. She embraces mom between the doors and they get emotional like for the first time. This time I’m ready – I take pictures.

There were the same worries and anxiety as the first time: you are again afraid to be infected, or to infect your close ones. The only exception is that in this case you seem to be more skilled and know more about protective means, you have better tools. It gives you as much comfort as possible in this situation.