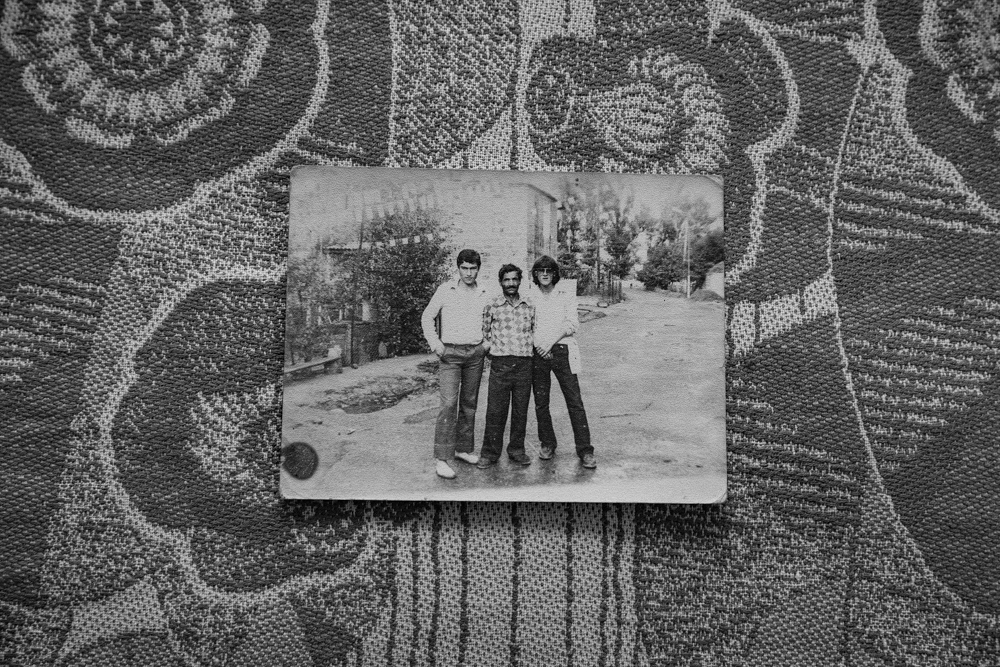

In October of 1993 the tractor driver of the village Khanjyan Vovka – Vladimir Gevorgyan – (until now everyone calls him Vovka in the village) left his family, his tractor and voluntarily went to Karabakh war with his village friends Ahan, Nver, Arthur, Lyova, Smbat. They got on the vehicle “Kamaz”, the trunk of which was the cabin of a worn out refrigerator like a zinc coffin.

“We were sent to Martakert from Karabakh, as it was called then – a people-eating place. In Martakert I understood why many men would hide in fields, why they would pass their nights outside, wouldn’t go home, not to be taken there.

There were no weapons. I was given a rusty AKM ( Kalashnikov’s Automatic Modernized Gun), the other guys were given AKS-s (Kalashnikov’s Automatic Folding Gun). The bullets for my weapon were lined up in sacks under the walls, but the bullets of the guys were counted. Each of them was given two bullets, with the words – one for the Turks, the other for yourselves.

When the moment of testing the weapons came, I was worrying – what if it won’t shoot, what if it will not function in the most responsible moment? I pulled the trigger, it shot so nicely, that I looked at it and said Natash jan, dearest, you are my friend from now on.

The sacred corner which Vovka made by his own hands for the icons of his mother.

The yard of the neighbour Radik.

Vovka’s summer hat and his cross.

There were no cigarettes. Once the guys brought a trunk of tobacco from the cellar of a Turkish village. Hand over and smoke, they said. Even the non-smokers stormed wanting to smoke, wanting their share. We would fill all our pockets with tobacco in happiness, a sea of tobacco, but you couldn’t smoke, there was no paper. One of us said that there was a Quran (the sacred book of muslims) in one of those houses. When we opened the Quran, the pages were very thin, just what was needed for a cigarette. I looked at the Quran, and said curse me as much as you want, I will smoke no matter what. We would cross ourselves before ripping the pages, then would wrap and smoke. That Quran kept our group smoking for two months.

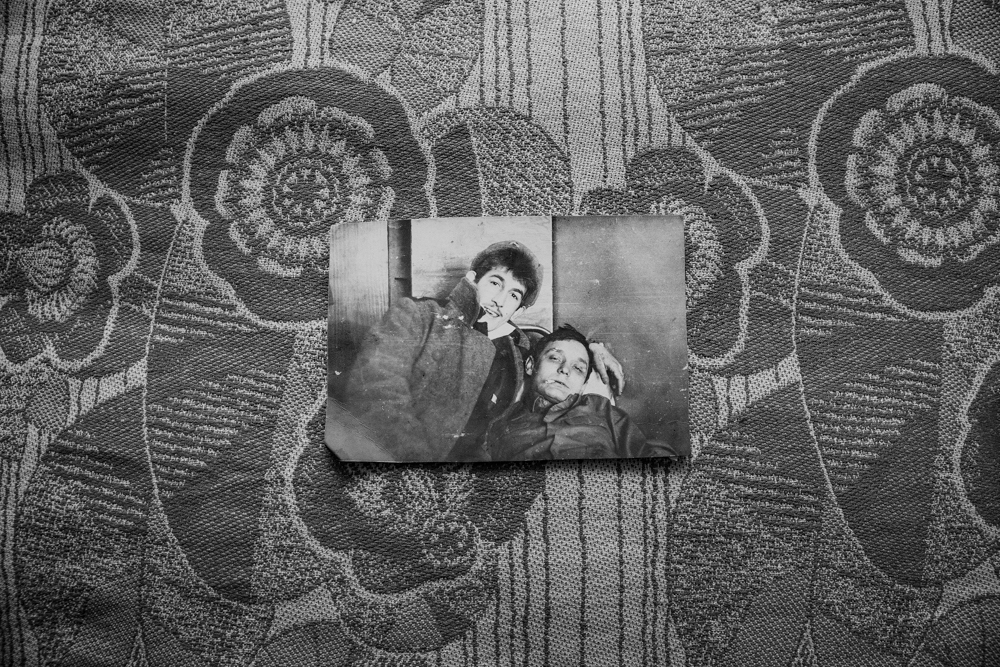

It was my birthday. We were lost in the woods hungry and thirsty. The guys said let’s reach the village, find a cat, make a barbeque, and celebrate your birthday. But when we reached the village, we saw a cat, which was so poor, that we pitied it, couldn’t raise hand on it.

In one of those villages one of our boys Lyova saw a pomegranate tree and said that he craved a pomegranate. He went to pick one, I said don’t touch it. When we watched the tree closer, we saw that it was wholly mined, the wires were sparkling in the sun. Tsigan said that it was a web, but that web would go from the pomegranate tree to wrap over the tree of almond, then to the fig, so we ate neither pomegranate, nor almond, or fig.

We would walk with our destiny with us. We would pass the mined wheat field with eyes wide open, we didn’t know where. It was our fortune that the field was wholly burnt down and the wires of the mines were seen. Four of the guys took one path, the other four of us took another. None of the four came back from that field.

The bombs would explode, hours were needed for the smoke to sit. Only our teeth were white, we were black. When we melted the snow, it would become like black car oil. You look at it, it is white, but when you melt it, you can’t drink it. We would find pitted stones to drink the rainwater from there.

Vovka at the TV set.

The cloth hanging from the fence is his clothing for working in the garden.

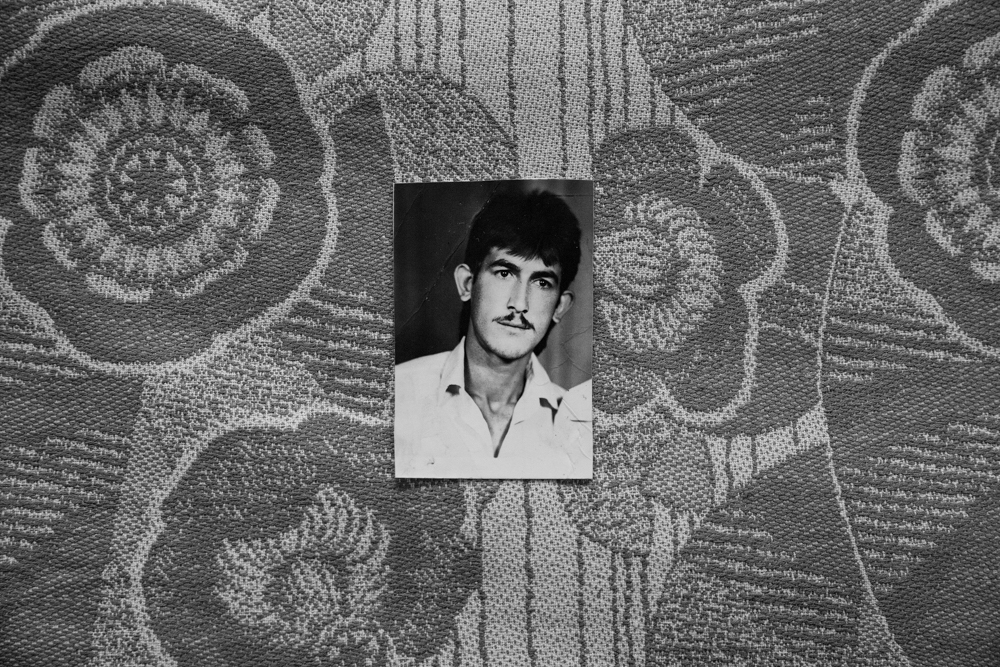

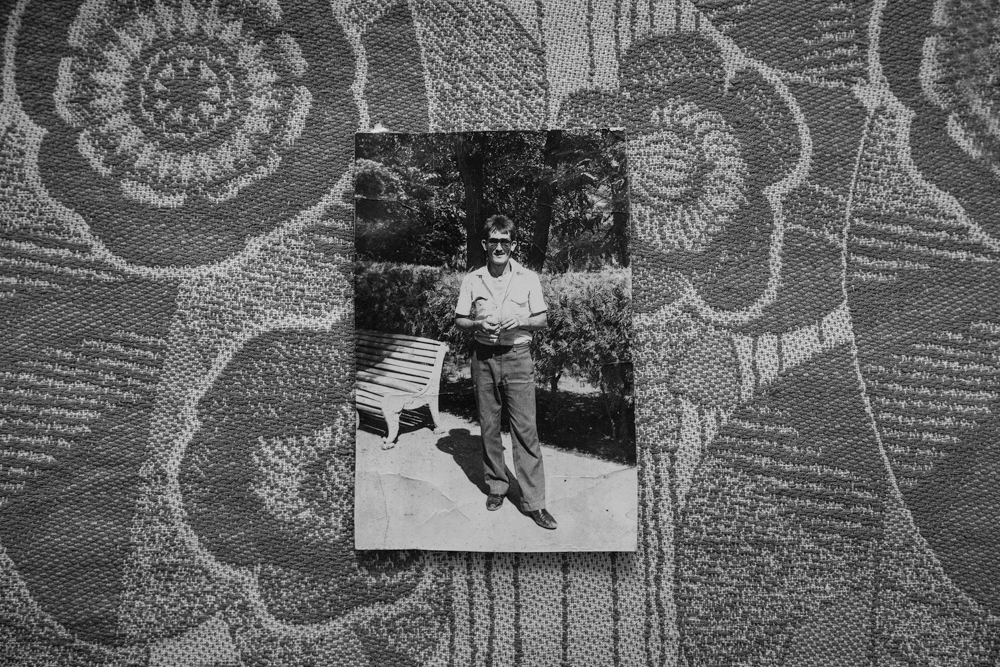

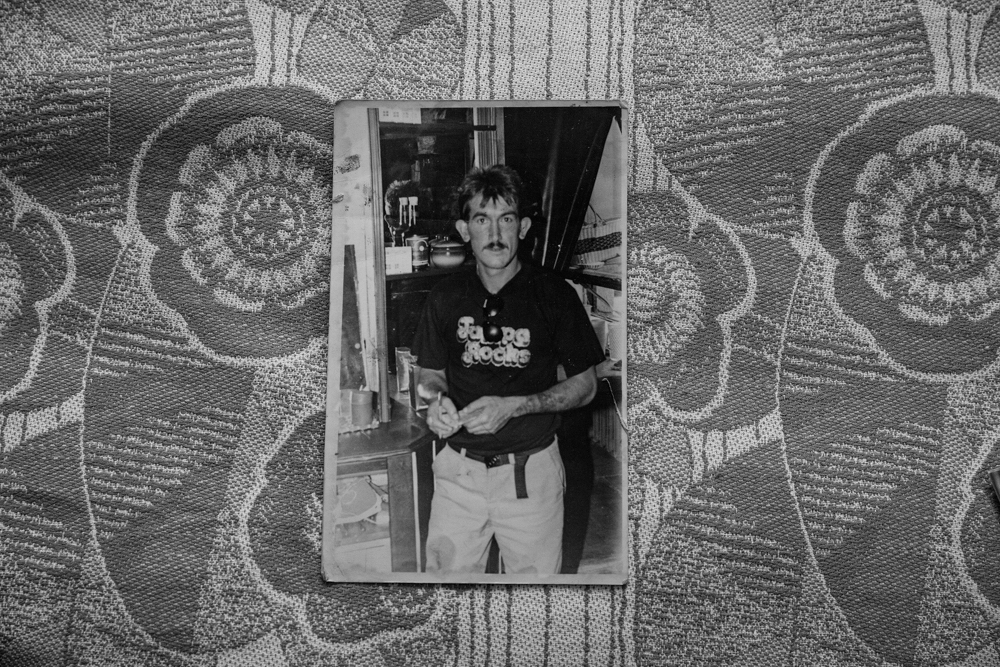

Vovka’s portrait.

Vovka’s medals for his martial service.

After my first injury they would say you will never die, I would believe. I didn’t go back home, I stayed there and treated my injury. My second injury was severe, I tied a piece of wood on my leg, and climbed for two days towards our side. There was no time for treatment, the doctors didn’t manage to treat everyone, they would ambulate immediately for the guys not to suffer. I was fortunate, they spared my leg.

My nickname was Yozhik (hedgehog) because of my hair standing upright on my head. During the battle there was a boy with his hair like mine. He died, his body was found burnt. When the corpse was taken to the base, they thought that was their Yozhik. He was placed into a coffin and sent to our village. The roads were closed then, it would take several days for a car to reach from one point to the other. By that time I was taken to Yerevan in a helicopter. It was dead cold in the helicopter, it was me there, some dead bodies, two injured guys, one of which died in the air.

When I was taken to hospital, there was no any connection so that I could inform my family that the dead one was not me. There was a policeman in the hospital, he worked in Hoktemberyan, I asked him to take the news to my family that I was alive. But as people say bad news reached quicker, than the good news. The village was already talking that my corpse was on the road, they had even cleaned the house with my wife and were ready waiting. I was lying for three days in the hospital trying to guess if the policemen ever took the news. In the evening my door opened, and the whole village filled into my ward. When the currency changed then, the price of petrol was 20 000 000 rubles, they had collected it in the village, filled into a car Vaz-24, and came to the hospital. I went back to the village with a disability of second category, my leg was shortened for 8 santementers. Harut, one of the guys of the village got lost without trace, some of the guys died.

A bed foreseen for the guests in the dining room. Above it there are the wedding photos of his son and his daughter-in-law.

Vovka’s guitar with its torn wires, his son’s wedding photo is there too.

Vovka’s portrait.

His renovated room with gypsum decorations.

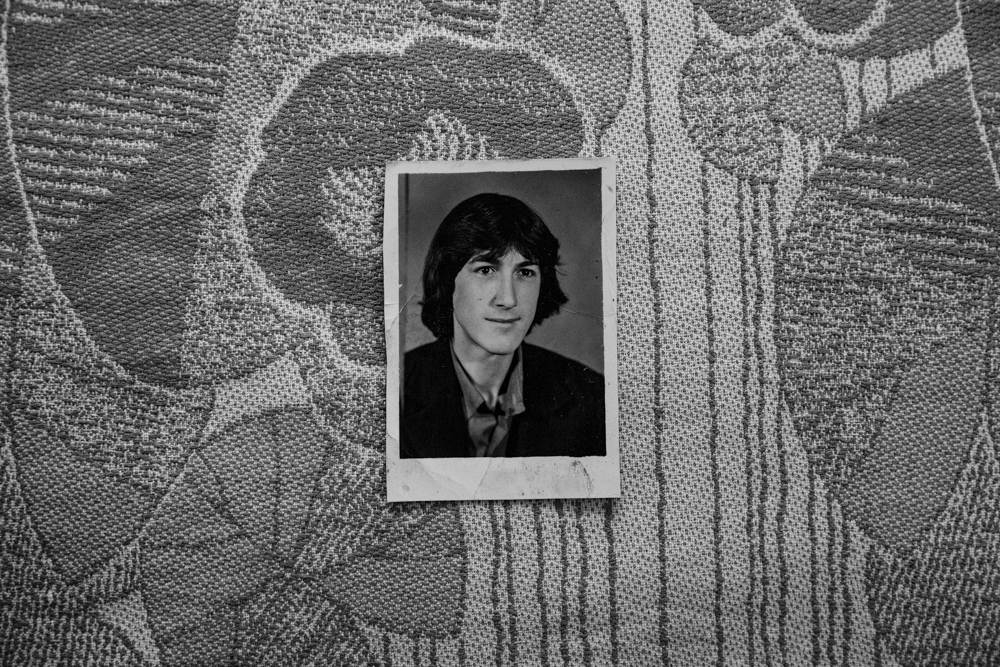

My childhood, my teenage years were not careless. I was 11, when my father died in his working place in an accident. My mother raised her three sons and one daughter alone. My father had met my mother in his army years in Altai region. He had fallen in love and taken her to Armenia. After ten years my mother died while working in the grapeyard. We were left alone. My sister was in her sixth grade, we sent her to live with my aunt, we were left alone with my brothers. I learned to look after myself with time, to cook, to clean, to iron, to sew.

One day my uncle said let’s find a wife for you, how long are you going to stay alone? You will marry, have someone to cook for you. Then he said you are not good in speaking, come along, let’s go to find a bride for you. In Akhalkalaki your aunt’s neighbour has a good daughter.

We went to propose her, but they didn’t agree. Her elder sister was to be married, then Varduhi. My would be father-in-law, who was a post officer, stayed stuck to his word, no and no, we won’t marry Varduhi while the other is unmarried, now go and come back in autumn. We had come a long road, we wouldn’t come back again, so we decided to kidnap her. Varduhi wrote a letter to her father that everything was according to her will.

We had two children – a son and a daughter.

Both of them went to Russia, to the city Krasnodar to work there and didn’t come back. My wife found a job in Ejmiatsin. She works in the chicken farm there, in greenhouses, she comes to the village several times a month.

Vovka with Sevo with the walking cane he carved.

The hall of the Culture house of the village Khanjyan.

I was left alone again. I bake bread once in three days, cook meals, when there is yogurt, I bake pies by the recipe of my neighbour Heghnar. I and Heghnar compete whose pies are better. In summer I do canning, make dry foods. I readjusted the old sewing machine of my mother four years ago, now I shorten my trousers with it. The curtains of the house I sewed with the help of that machine, it was more difficult before, I was sewing with hand. After marrying I decided to renovate the house, I made small decorative details of gypsum for the ceiling and the walls. I used to make wooden table, furniture, carvings, I can make shoes, do masonry, drive a tractor, cut hair. Even now some of the villagers come to me in summer to have their hair cut. Perhaps I have done everything besides piloting an airplane.” I asked about the guitar standing in the corner of the room, he said yes, I play it, but the wires are torn, I can’t play it now.

“I mostly watch TV at home, you won’t see anyone in the village in winter, in summer people go to the mountains, the village is empty. When it is sunny, I come out and sit at the gates with Sevo (Vovka’s dog), and watch the empty road. There was a time when the street was paved, lighted, children would play in the yard. There was a library in the Culture house of the village, a cinema, concerts, there were performances. Now there is only dust instead of the audience, and people watch their lives pass by on TV shut in their homes.” At the end of our conversation he said let me fetch a pomegranate for you from the cellar. I asked if it is a real pomegranate, or just a grenade, will it explode? He said it will explode, but only from its sweetness.

When I was strolling in the village and rolling the tape of this story back and forth, I suddenly appeared in the empty streets of 1993, I noticed the abandoned tractor, the poor cat, the VAZ-24 hurrying to the hospital… It seemed that the village having sent his sons to the war was holding its breath waiting them back.

One of the streets of the village Khanjyan.