Image: Hrayr Badalyan

Life in Artsakh had many layers: war and peace; development and fall; liberty and blockade; achievement and loss. In a life full of paradoxical contradictions, Artsakhians dared to be happy. But their happiness was fading away.

Confinements gave little chances to be happy – power is back on; the rain falls in a downpour, which means that the Sarsang Reservoir will be filled with water; the Hague Court has imposed sanctions against Azerbaijan; humanitarian aid is in Goris; your number is called out in a bread queue…

In the last months of 2023, there was almost no reason to be happy in Artsakh, but there was Artsakh…

When forcibly displaced, all that the Artsakhians could fit in their cars, was fitted in their hearts and souls. They arrived in Armenia burdened with pain.

Artsakhian photographers were documenting their homeland in their own way: colorful and bright, suffering and groaning with pain, living and struggling.

Later, not only memories would become the only way to return to the homeland, but also photographs, which are a window home, to the invisible homeland.

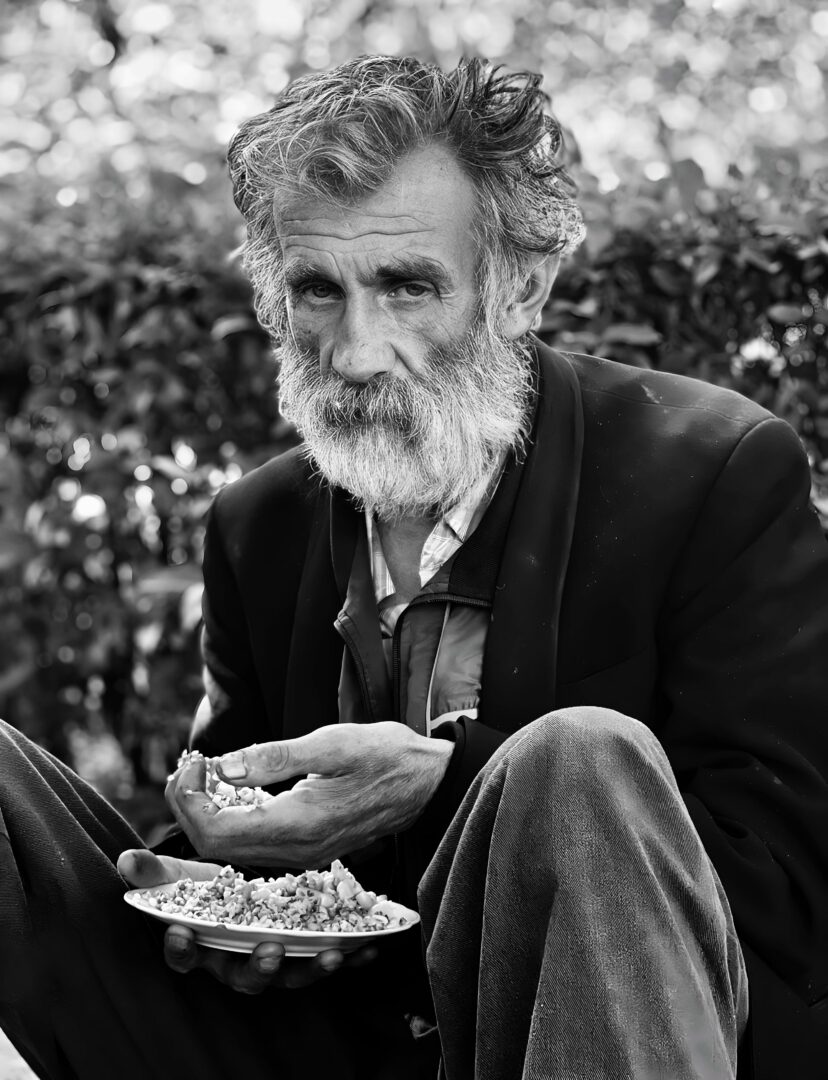

Hrayr Badalyan

Photographer

I am not a photojournalist working on efficiency or sensationalism. I document history.

I rarely took images of my acquaintances. I would rather capture random passersby, those who embodied the essence of the present moment and present-day reality.

My photographs were not intended for Facebook likes. I have got many images I have never published. I am waiting for the right moment to organize an exhibition. I am sure my compatriots would be happy to see themselves in these photographs taken in Artsakh (maybe because they will never have the chance to be there again), whereas back then, they would not allow me to take their pictures or forced me to delete those images.

During and after the blockade, people would not trust anyone, including the photographers. Whenever they saw a camera, they became anxious, alarmed and irritated. Perhaps the first reason was that they were too exhausted, not cared for and tired. The second reason was that they had become a target for the enemy and were victimized by the manipulations of the mass media hunting for sensations. Of course, I understood the situation and respected their position. I was very cautious in taking photos.

During the last days of September, I already realized that it was the last time I was taking pictures. I was doing my best to capture everything, to be everywhere, but I could do so in Stepanakert only, as I had neither fuel nor opportunity to go anywhere else.

I focused mainly on the monuments. I knew they would destroy them first.

During the explosion, I captured a tremendously agonizing moment: a dead man lying between the two columns. That breathless stranger seemed so alive. It was a terrible situation. I would have never thought I could photograph something like this. If it happened a few years before, I could not photograph, but in the past few years, we’d witnessed so much cruelty, hardships, horror…

There was soot everywhere; the site was dangerous. I was shooting the invaluable work of the rescuers. I knew that if I asked permission from them, they would deny me, while there was no time to explain to them the significance of documenting their actions and my desire to immortalize them. I was shooting without permission, often stealthily trying not to distract them from their mission.

Armen Gabrielyan

Director of the Puppet Theatre “Sprout”, Photographer

I fell in love with photography when I started taking pictures of my hometown Shushi.

At one point, I realized that I had to document Shushi’s unique architecture and to show its rich history. Shushi was also its people. Each of them embodied the history of Artsakh. I started telling their stories through the wrinkles on their faces, through the droopy eyelids, burning and faded gazes. I was photographing them.

I was taking their pictures and feeling awkward at the same time…

My camera captured an old man eating pasta with hands. I was doubtful whether or not to photograph him… People reacted differently. Someone shied away from the camera, the other was drowned in grief and would not even notice the camera.

At the end of the square, one of the women was handing out cooked pasta to people who had been in the square for a long time. The old man was one of them. I thought it was the Government’s initiative, but then it turned out that the woman was giving away her own food stocked for winter.

I realized that in a few minutes it was my turn to leave my homeland, and if I were lucky to find something to eat, I would eat with hands, just like the old man.

Stepanakert’s Renaissance Square was unrecognizable. People were waiting for their turn to leave their homeland in despair. There were mainly displaced villagers from the regions of Artsakh and me with my camera. My lens captured the mood of Artsakh of the day: poor, awkward, weak…

I was criticized a lot for publishing these photographs. However, no criticism could compel me to stop presenting Artsakh left alone in its pain and suffering.

Hasmik Khachatryan

Photographer, camerawoman

After the 2020 War, when we returned to Artsakh, I wanted to photograph everything.

I wanted to fit Artsakh in my lens. I am an amateur photographer, I took images for myself and did not publish anywhere. Today, my photographs are published in CivilNet’s #memoriesfromArtsakh section. I managed to be in many parts of Artsakh while working at CivilNet.

During the months of the blockade, I was documenting everything. I was trying to show the events taking place in Artsakh to the world. We were cooperating with international media. It was difficult to work under the blockade. We were able to film only in Stepanakert, and we had to walk from one end of the city to the other carrying heavy equipment.

After work, I was a regular Artsakhian and was going through the hardships like everyone else. I was either photographing the queue or standing in the queue.

On September 19, when the military attack started, I was at CivilNet’s office. I grabbed my camera and my laptop and went to the bomb shelter. I sat frozen for the whole day and did not photograph anything… Maybe because I was first of all Artsakhian whose family was parted. My brothers were at war, and we had no news from them.

If I didn’t have my job, I would probably not have photographed anything.

On September 20, I got over it and started taking pictures. First, I was shooting the shelters, then our rented house in Stepanakert, where more than 70 people had taken refuge after the evacuation of Martakert region.

I would go outside and walk for hours in Stepanakert. I was taking pictures until the batteries in my phone and camera ran out. We had no electricity and internet in those days. A “Dvijok” (an electric generator) was turned on in a few spots in the town, and everyone was rushing there. After waiting in the queue for hours, I could charge my equipment and rushed to take pictures again. I didn’t want to miss anything. I knew I wouldn’t get a second chance. However, even now when I look back, I regret not taking more photos.

Sevak Asryan

Landscape photographer

I started photographing Artsakh from 2016. Before that, photography was a hobby for me.

I was taking pictures when we were hanging out with friends, hiking or just having a trip retreat. Later, I made up mind to discover Artsakh for myself through photography.

Artsakh was known for Dadivank, Gandzasar, Amaras, the two churches in Shushi – Kanach Zham and Ghazanchetsots or Holy Savior Cathedral.

I tried to show other Artsakh, other world. I did not want people to see my country wounded, destroyed and miserable. My photographs were about living, laughing and dreaming Artsakh. My photographs were bright, colorful, full of joy and life.

Once I shot Shushi Kanach Zham from a completely different angel and forgot about that image. I recalled the moment I was photographing it and the road to the church. Though Gazanchetsots is one of the landmarks of Artsakh, Kanach Zham is one of the most beloved churches of our people. It was bombed during the 44-day War, and when the enemy took control of the church, it was relentlessly destroyed.

After publishing the picture, my compatriots texted me saying that Artsakh for them was Kanach Zham as well…

I cannot erase a picture, even the bad ones. To get a single photograph, you take several shots, select the best ones, and delete the rest. I cannot delete even the bad shots now. Our life is in those images.

Following the first days of the forced displacement, it was extremely hard to look for an image in the archive. I was rummaging my archive to find two photographs and was experiencing everything again, my mood was falling, I felt depressed…

I had a hard drive where I had stored images taken in 2018 and had forgotten about them. Before leaving Artsakh, I managed to find the disk and take it with me. I did not remember what was inside, but it was important that the enemy did not get it.

I had made the right decision. There were more than 1000 images in it. I found photographs that made me happy.