I took three pieces of clothes, my camera with a discharged battery pack, and the worst lens… I left the house and set off…

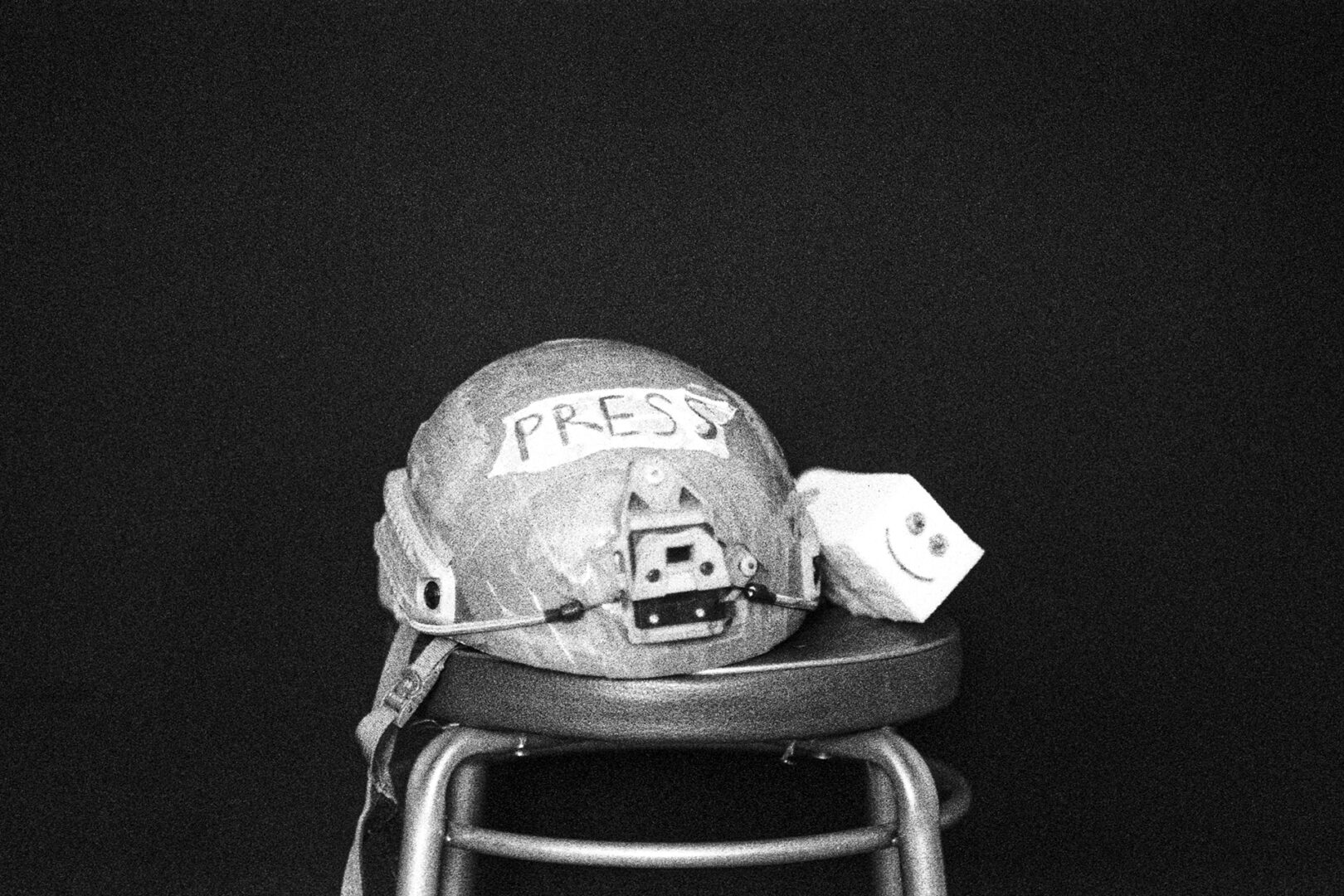

․․․When the Azerbaijani forces hit Martuni, it was very close – five meters from the missile strike… My friends Areg, Khaneh, as well as French journalists, who were injured, were on the other side of the road. A man from Martuni, who was guiding us through and showing the damaged houses, pushed me to the bomb shelter… that is how I was saved.

Martuni was the most horrific place. It was that very same day that I realized and accepted that I could die. After that, it was easier… You start doing your best, as other things are beyond your control.

Prior to going to Martuni, I was sure I had to go back to Yerevan, because I thought it was not a place for me to be. The journalists would mainly run to cover explosions, whereas I didn’t want to do the same… I was thinking maybe, in the meantime, a couple was sitting in a bomb shelter, and the guy was in some way persuading the girl to let him go… This was more important for me than running after an explosion, but there was a foolish competitive race I could not understand. I would say no, this was not my place, I’d better go.

… But I just couldn’t. People, whose names were unknown to me, and who had saved my life, had given me water, medicine, everything… They even kept watch over me when I would go to the loo, so that I wasn’t scared…

When they launched aerial bombing, the ground beneath my feet trembled (I am terribly scared of earthquakes), and I left for Goris… I remember I was writing a letter to Khaneh, telling her, “We are dying, Khan!”… I stayed in Goris for a day. I returned to Stepanakert… Because my friends and my brother-in-law, who in fact was wounded on the third day of the war, were there…

We were making jokes, but we realized we were short of regular things. Say for example there should have been sanitary napkins in the first aid kits, because we couldn’t get them anywhere… I remember Areg’s friends were going to send relief items, and he had told them to send sanitary napkins as well. Imagine, the boxes arrived and while handing out one to an old man, Areg took a pack of pads and said, “here you go…” And there were some six people around…

War is a compressed life, you see… There is everything there, not only fear, horror… There is life, it goes in parallel with war… Humor (so many jokes were told there, perhaps in no other place), sharing bread together (we had to think what to eat and how not to leave anybody hungry), solicitude (whenever you saw a soldier, you wanted to fill his pockets with all you had)… You live up your life in a compressed and fast-paced mode. It is only a question of how long will you stand and be ready to see so many things within that short timespan?

The paradox though is that before surviving a bombardment, I took really bad photos, as I had to run. It was impossible to apply optical exposure, the frames were awful, my lens was awful… It was on the way back from Goris that I started getting concentrated on the work. While I was choosing the right focus mode and exposure, shelling would stop… In fact, it was the first time I was shooting on my own, managing the whole process…

…We were evacuated on November 7th, and it was signed on November 9th…

… Evacuation… It is my shameful day… The long lines of cars driving off… It was harsh. It was dreadful. A soldier told me, “Leave, we will keep the land.” They were heading to the city, while we were leaving… I think I will always walk by these twenty-year-olds with a lowered head… But at that moment I realized how important the rear was for the soldier; how important it was when the city dweller stayed…

The war took from all of us.

It took away our spontaneity, no matter where we were.

It brought a sense of guilt…

Love grew ever more. I felt I could love others, not only myself and my family… I think I should have kissed those 18-year-olds… I don’t know… My friends who were with me, the parents who consoled me… There was a moment when I was crying, and a parent of a missing in action soldier came and hugged me.

I remember when I was shooting the non-evacuated mothers (they had refused to leave, as their sons were there) in the bomb shelter, they asked me if there was any news… They thought I knew something. I was shedding silent tears after that question standing behind a column and thinking that no one would see me, while they did and brought me a blanket and tea…

It is something beyond one’s power when parents, who have no news from their sons, take care of you.

They would reluctantly send me to the front line, really… For the sole reason I am a girl… But I found ways; I approached the foreign journalists and told them I would accompany them as an interpreter. I got in the car with the Russians and left. We had long debates if it really mattered who saw bodies, I or… The men had their reasoning; they said, “You will bear a child, the navel cord is in you”, and that they didn’t want that memory to pass to the generation… I could say nothing.

We all are in a shit, we are in the same boat, and it’s hard to understand whether or not someone is in a better position… I mean the normal has become so abnormal in our society, that we are unaware whether or not we are all right. I really don’t know… I have seen a therapist; I have talked to her. She told me it was difficult to understand the impact within such a short period… I know one thing: I cannot live another minute without Artsakh… I cannot sleep… I can’t shut my brain off for a second.

I am not the one who covers the war and have never been. Ես պատերազմը լուսաբանող չեմ եղել և չեմ։

This time, I went there, because it was important, because no one spoke out, there was the COVID and I don’t know what else․․․ No one came. In the first days, I had some cooperation with the Associated Press, I gave some materials to NHK, wrote a post on Facebook, thinking that international friends would somehow react, because it seemed to me I was doing an important job… It all changed after Martuni. I rejected anyone who asked for materials… The scale of the risk made me not do things I didn’t want to…

We didn’t set standards for victory and peace…

Areg said we had to first define our standards for claiming peace and victory. Did “We will win” mean 30,000 victims? Are we ready or not to have so many victims? Does “We will win” mean no victims or return of territories…? Does it mean having a strong state or being someone’s subject…?

I have seen a veteran with two crutches who had to drive his flock to mountains, where the Azerbaijani military posts are one meter away. He has to guide the flocks so that none of them pass the other side; he has to be in the mountains all day long… This can’t be peace…There is no peace when they open fire towards our positions, whereas there is a “Cease fire” order from our end, lest the war resumes… There is no peace if you have to remove the small flag from the windscreen of your car when passing through that corridor (the Lachin corridor)…

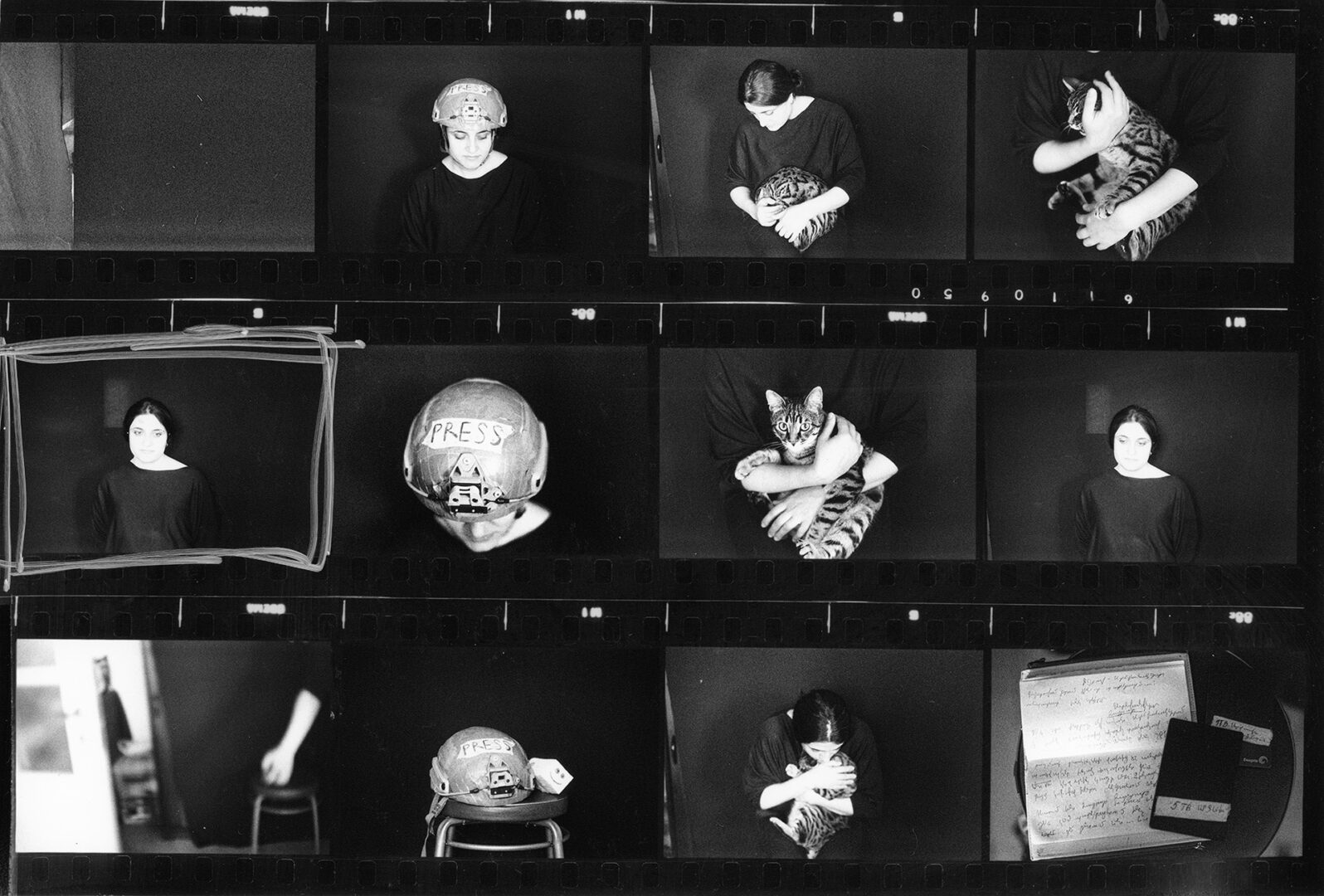

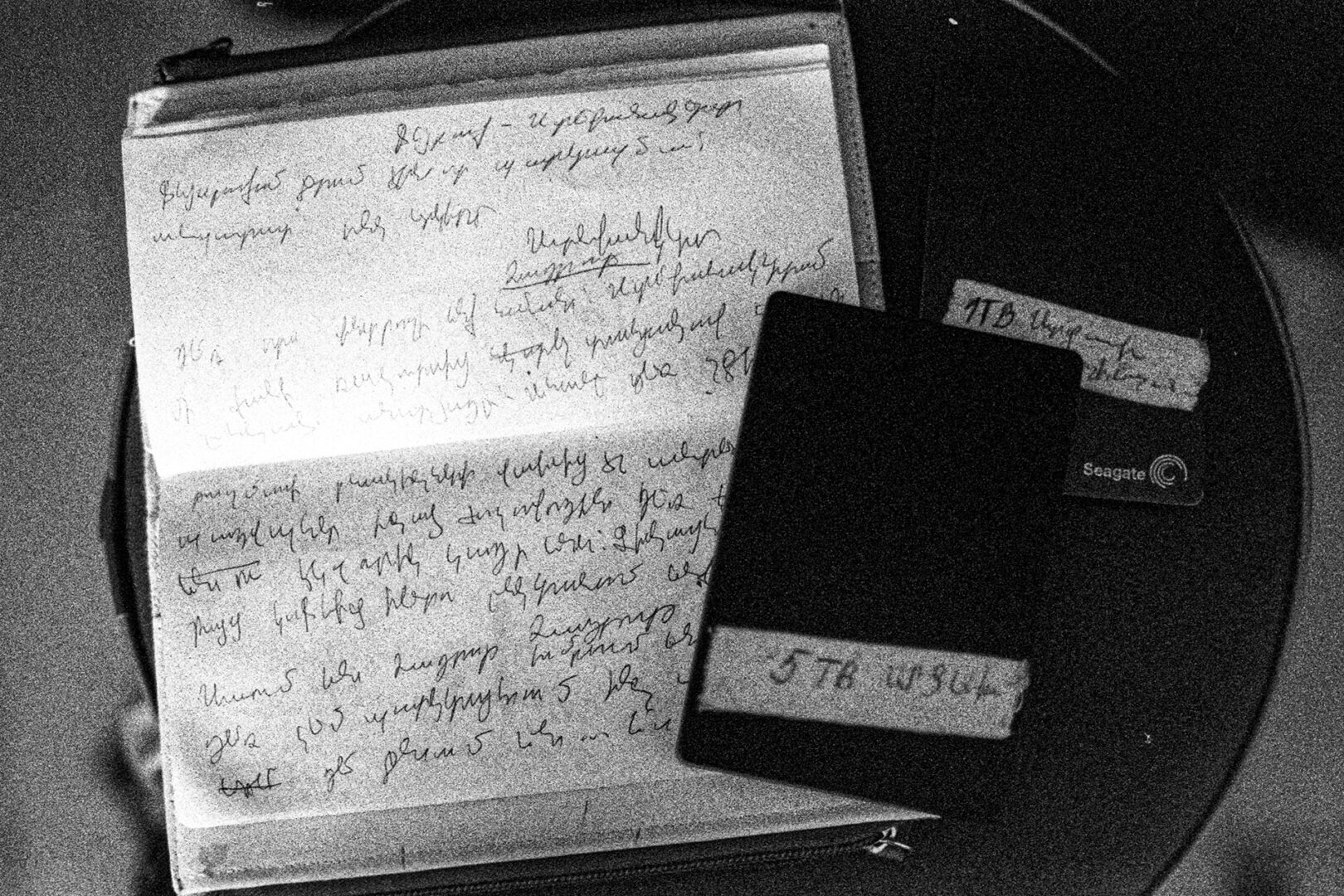

The photographs I have taken are very intimate, firstly, because it was only me who took pictures (there was no cameraman), secondly, I let myself just shoot, and thirdly, I didn’t know whether or not I would survive. I wanted each frame to be great, and I would never think that those images would be for “sale”.

It turns out, it is the woman, who went to war for 44 days and kept a “diary”. On the whole, yes, it’s my diary, and I think it’s good that the diary is about everyone… It is about people who could talk with the woman …

It is about those who I lived with and saw in the military posts. It is about a doll, I saw in one of the posts, and when I enquired about it, I learnt everything about the lives of those guys – who was married, who was not, who was about to marry but couldn’t make it, who shied away from the camera, because he had messy hair, he was dusty and didn’t want to appear like that before a girl that was waiting for him…

I don’t know if it’s a movie or not…

It’s a genuine and intimate process…