Media professionals often read, watch, hear, write and tell harsh stories happening to others. One would think we are hardened, our emotions immunized… But at least for me, it is not like that anymore. It is not like that after the latest war in Artsakh. I feel emotional even when watching a cartoon with my five-year-old son, when the scenes lead up to climatic parts, positive though.

I am sure many of my colleagues have become emotional like me after the war stress they have experienced. Perhaps their professional “immunity” has even temporarily weakened.

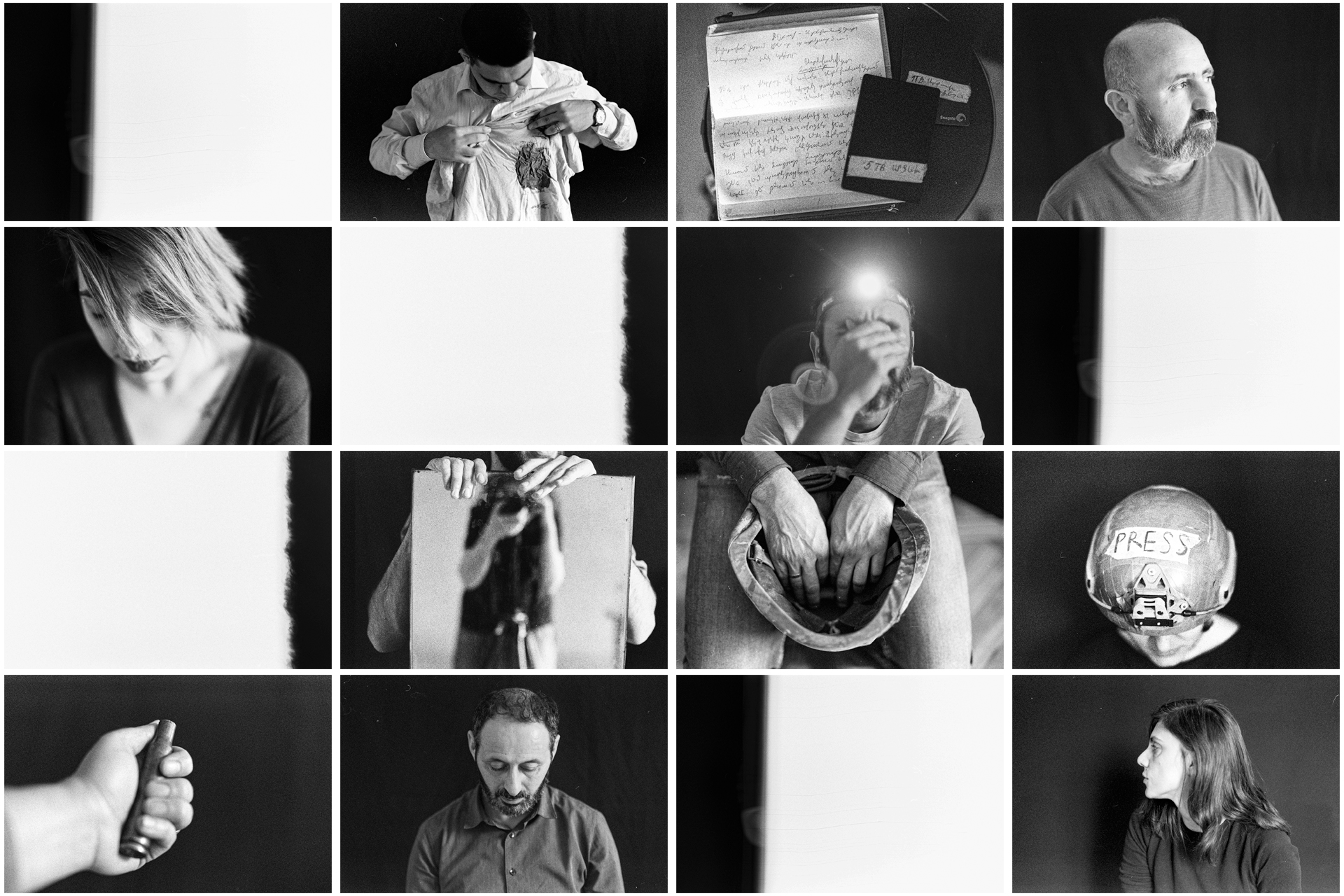

It was on March 9, 2021, another late night (the days seem longer since the war at the cost of sleepless nights), when I saw Anush Kocharyan’s post on Facebook about Nazik Armenakyan’s “Red Black White”–(I am not going to retell it so you read). Well, Anush writes in such a way that one is intrigued to click and read.

That night I read the story and got to know those four women, whom Nazik presented so cautiously and with particular delicacy, the way only she can do. She tells about the tragedies of her characters in simple words, without unnecessary epithets.

I read and cried. I did not get emotional, I cried.

After having read the “Red Black White”, I realized that Nazik is the one to tell about the group of our colleagues who had direct access to the conflict hotspot to cover the 44-day Artsakh War of 2020 and its aftermath.

As an editor and an author of media projects, it is not within the scope of my interests to present stories about journalists telling about their peers and preparing journalistic materials. I think media people should first of all talk about problems, pain, and achievements of other people, that is about others’ life.

I am grateful that Nazik agreed to work on this documentary, which hopefully will somehow mitigate the stress of the war in the memories of the characters of this photo story… After all, telling can heal, can’t it?

Seda Muradyan,

President of Public Journalism Club

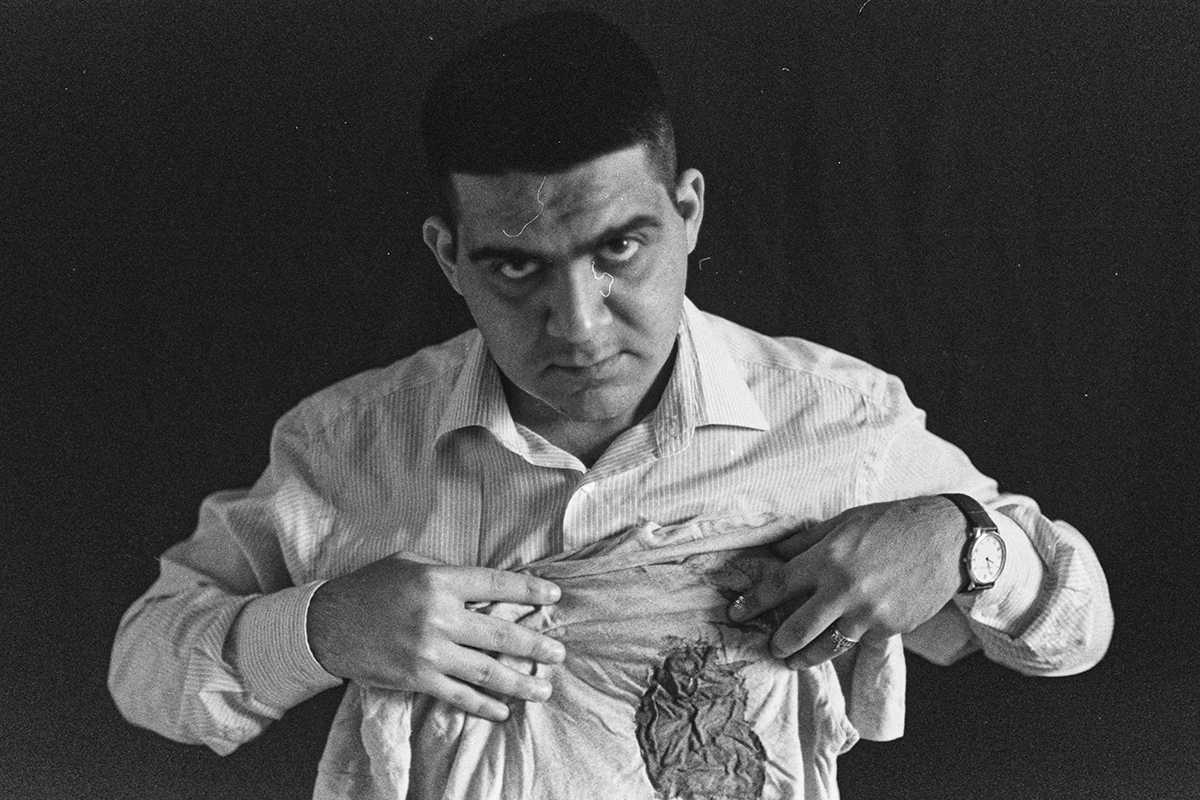

I fought my war… First of all, as a mother, not as a photographer.

September 27 was my elder son Mikayel’s birthday. The day started with terrible news… Friends, relatives and guests gathered at our place, and the phone calls from the military commissariat started. He was called for conscription.

We went to the military commissariat in the morning of September 28 and Mikayel was taken away…

Only when I was back home did I realize what was going on. Read more

Co-founder, 4Plus Documentary Photography Center

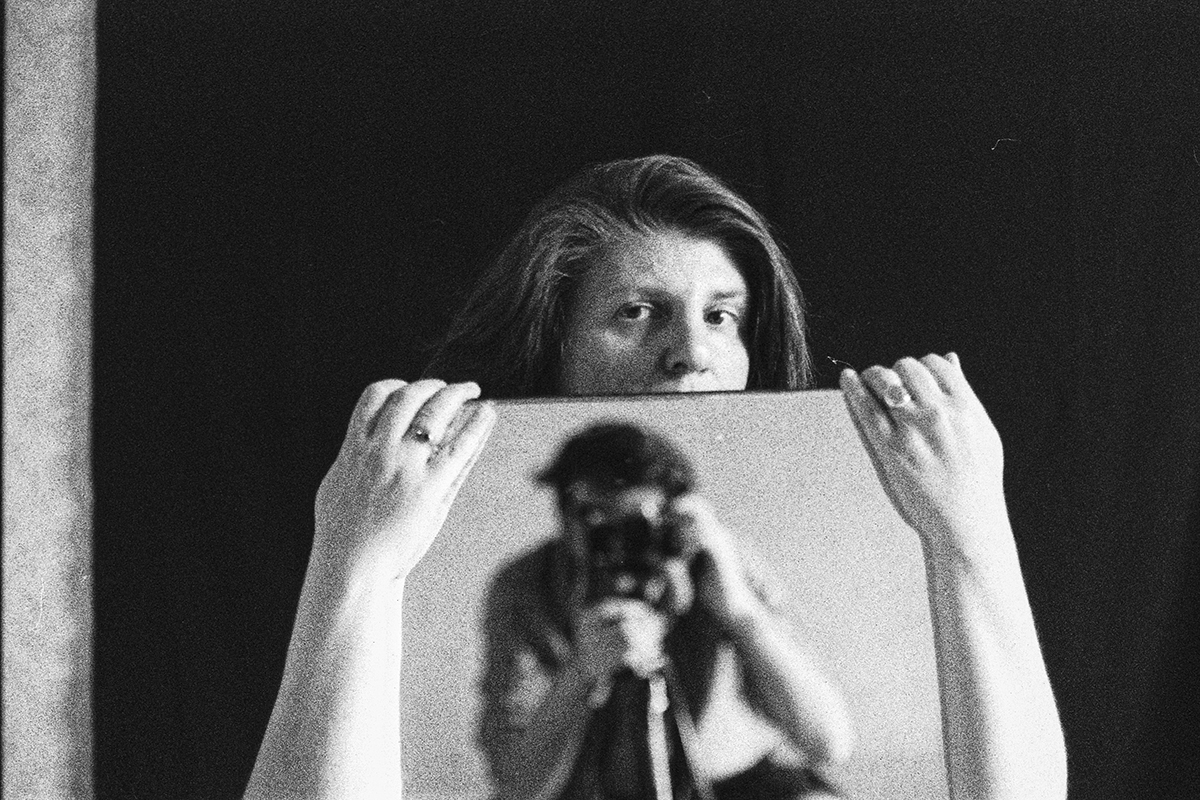

․․․ With either the camera or arms, I had to be there…

(That is how I set off taking my military ticket with me, so that if need be to take the arms, I would put documenting aside. I was thinking maybe it would take long, until spring, and I would take as many photos as I could, and I would fight once there was the need for it…)

Shooting was fighting in a way. I was fighting at least with the camera…It was like keeping a diary: I would wake up, decide to go this way or that way, and take photos on the spot… Read more

War is a compressed life, you see… There is everything there, not only fear, horror… There is life, it goes in parallel with war… Humor (so many jokes were told there, perhaps in no other place), sharing bread together (we had to think what to eat and how not to leave anybody hungry), solicitude (whenever you saw a soldier, you wanted to fill his pockets with all you had)… You live up your life in a compressed and fast-paced mode. It is only a question of how long will you stand and be ready to see so many things within that short timespan? Read more

You take your belongings and leave the house, and so it begins… Psychologically, you start to accept that you are going to war, and it is very likely you won’t come back. This is the first barrier, an inner process, which…

… It becomes a regular thing, as if it is the way it should be; you get used to living under those bombings, siren sounds, whatever… Say, when living in the city, you don’t think you are going to be crashed by a car today, do you? Or that the cable of the elevator will break and you will die, you don’t think of that, do you? You simply accept the reality you live in; you choose to either stay there or not, and how long to stay… Read more

Over time you understand what is allowed and what is not. You train survival skills and learn to dodge the danger. You think you cannot overcome something, then you see you passed it like a test; you saw what happened and made a decision.

In fact, the most difficult part is treating the situation as a job, when it concerns the lives of people. You haven’t lost your house, you cannot be in the shoes of a person who has lost his house… Covering misfortune of people becomes an issue, and you face the dilemma – “Well, what am I doing here? How am I doing it? Am I doing it right?” Read more

… When I went down to the shelter, (it’s cooler there, isn’t it…? It’s cold. It’s a basement after all), I felt some heat. I put my hand on my back, and saw blood. I said, “Well, maybe when the computer fell from the desktop, I got a scratch.” I took a deep breath, stretched my hand higher and felt the opening ․․․ I was wounded. Read more

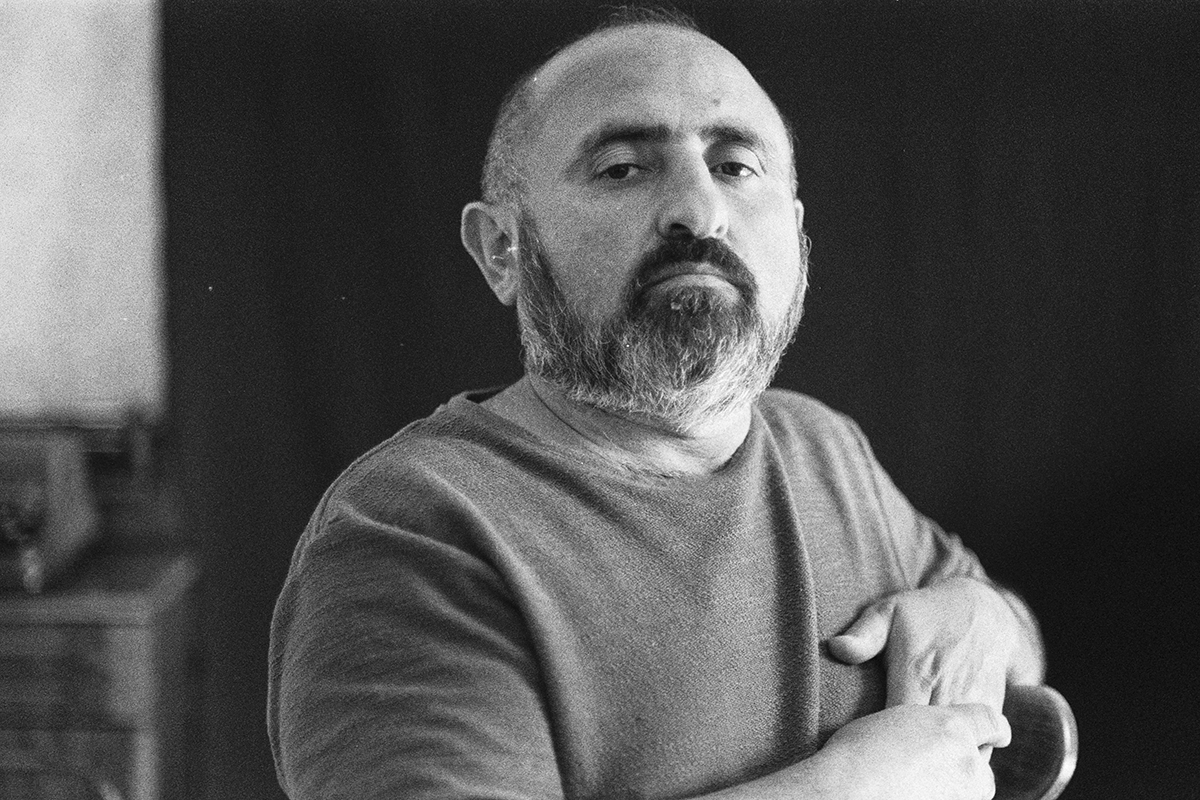

I think journalists were simply hamstrung during the war. You have a certain mission, and so you go there with an idea that you should be one of those to document the war, the one to tell about it to the world, but no one thinks so except for yourself…

You realize that this notion is only in your head, that it’s your choice, because the guys are fighting, others are doing their job, and you have to do this, that’s your duty… Read more

Armenian journalism lost because we were not fearless enough. Now, I blame myself every single day. Yes, I shouldn’t have been scared… And if my colleagues and I worked well, probably the people would start thinking in a sensible way, perhaps there could be other solution, perhaps the loss wouldn’t be so painful…

․․․ And I don’t blame the authorities for the bad work, neither do I blame Artsrun, nor the Armenian community of Facebook. I blame ourselves for not having enough courage. Read more

The publication was prepared in the framework of “Rapid Response Fund Initiative” program, implemented by the Public Journalism Club, with the financial support of European Endowment for Democracy Fund (EED). The views and opinions expressed in this material are those of the author and may not reflect EED’s official position.