Eva – The first

Eva was the first among the women and at the Kristapor Ivanyan Military College in Stepanakert. The college began admitting girls for the first time two years ago. Eva Ghazaryan was one of three girls who were admitted.

Eva’s the only girl in the 12th grade. She stands proudly before a backdrop of green–light green–light brown camouflage clothing, the sole exception, wearing a ceremonial black military overcoat, her long hair in a bun at the nape of her neck. Her hat is the right size, but the overcoat is long at the sleeves and a little wide.

“The little soldier,” I think.

She smiles lovely. She is the pride of the boys in the platoon.

Eva Ghazaryan’s portrait. Two years ago, the K. Ivanyan Military College in Stepanakert organized an open house for women. Eva was one of the first three women admitted.

Eva is coming back from the cafeteria with her course-mates.

At geometry class.

Eva during military training class.

During the break.

Young cadets are going to the classes. Eleven female cadets are currently in K. Ivanyan’s Military College in Stepanakert.

The entrance to the K. Ivanyan Military College in Stepanakert.

In the cafeteria of the K. Ivanyan Military College in Stepanakert.

Girls wearing their ceremonial black military overcoats.

In the evening, on the way home.

Eva’s tricolor hairgrip.

“I didn’t think long about being admitted to the college. I knew for sure that I wanted to be a military lawyer. Then it became clear that I can’t get higher military education in that area yet — neither Armenia nor Russia offers admissions for girls in that profession. I was forced to choose missile defense,” says the girl.

She enters the cafeteria with boys who’ve just begun to shave, sits at the end of the table. Her classmates know that Eva doesn’t eat onions. They remove the chopped onion from the salad and only then pass her the plate.

During the break, between the bunk beds in the small room there’s a non-military ballyhoo. One of the girls is braiding another girl’s hair, the third is preparing her textbooks for inspection, while another is playing songs on her phone.

Besides academic performance, physical training is important at the college. Eva and a few women participate in combat training (hand-to-hand fighting).

Eva during the break. Eva Ghazaryan, 17. Two years ago, the K. Ivanyan Military College in Stepanakert organized an open house for women. Eva was one of the first three women admitted.

Eva during military training class.

Besides academic performance, physical training is important at the college. Eva and a few women participate in combat training (hand-to-hand fighting).

Eva is organizing the certificates she collected with care in a thick folder. One is for singing well; the other, for athletic achievements. They don’t want to lie down in their ceremonial uniforms; they wrinkle easily. But the fatigue does its part: they sit down leaning on each other for support on one of the beds and begin to sing.

Of the college’s 11 girls, Eva is the only one whose family was not against the daughter’s choice. Her father, uncles… all are soldiers. She studies because she knows that this war needs a political and legal solution. Living in war is already impossible.

“Eva, why do you study? For war?” I ask.

“I have not seen peace. We’re on the border. One day good, one day bad… For us the ‘first level of combat readiness’ regime never stops. That’s our life, what can we do? We need strong and smart people behind us, decision-makers, giving instructions. The rear has to be strong,” she says.

“To be ready… and with the hope that what I’ve learned won’t have to be put into practice. I don’t want war, but this issue is not being resolved at a political or legal level for 23 years already. This war is older than I am,” says Eva and smiles again. On the other side of the door with a glass window is her father’s contour. Today is a ceasefire at their home, until 6:00 a.m. the next day, when the war will take her father again to his military post and her to military college, to learn for peace.

Kukla Babo – Winning the fight, losing at life

Everyone in Shushi knows Yevgenya Arstamyan. Beneath short white wavy hair and wrinkles lives the city’s most beautiful woman. A granny who is still called Kukla (Doll).

The cleanliness of the large, spacious house is astonishing. It seems she was waiting for guests. In one room is the wood stove; in another, the television. On a small table next to the TV are two photos: one is of her at age 16, without make-up and lovely.

Yevgenya hanging the laundry.

Yevgenya is putting lipstick. Everyone in Shushi knows Yevgenya Arstamyan. A granny who is still called Kukla (Doll).

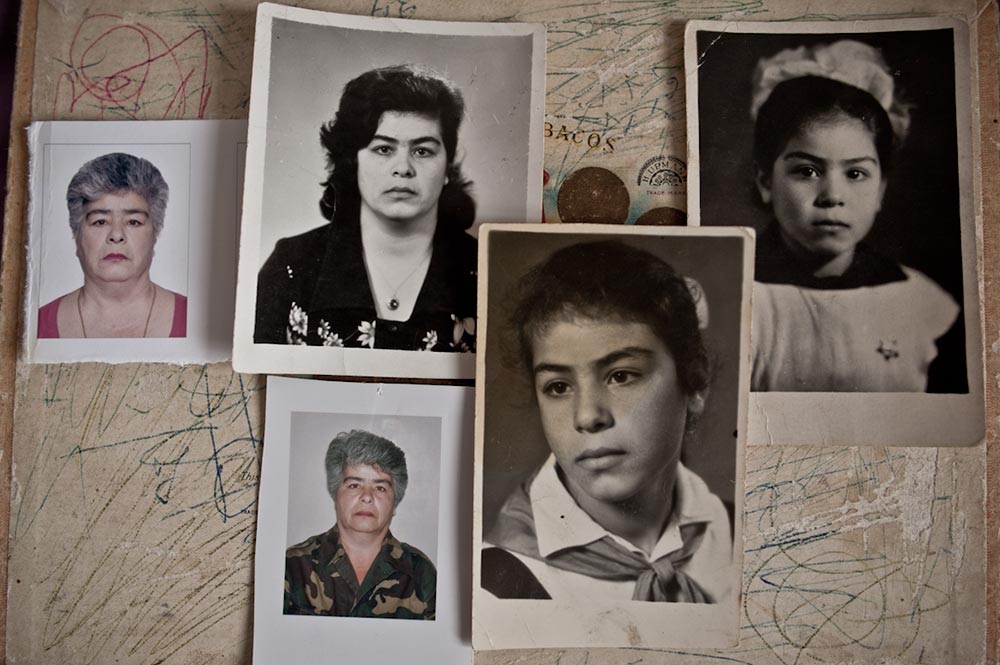

Yevgenya’s photos.

Yevgenya in her kitchen. Everyone in Shushi knows Yevgenya as “Kukla Babo” (Grandma Doll). Karabakh War veteran, sniper.

Yevgenya is showing her tombstone.It’s already several years she has put hers next to the tombstone of her husband.

Yevgenya with a photo of her younger years.

Yevgenya is talking to her son, who lives in Sankt -Petersburg.

The bedroom of Armen, Yevgenya’s youngest son. The official version of his death is the suffocation from fatal gas leak in 2015.

Yevgenya holding her son’s photo. The official version of his death is the suffocation from fatal gas leak in 2015.

“It’s my Armen. My youngest. He is a strong-boned boy. Look at the color of his eyes — how beautiful it is. He died two years ago,” says the granny, showing the other photo. His son is smiling, wider than people usually smile in photos on gravestones.

“Grandma, did people fall in love with you often?” She responds to the question: “No, they didn’t risk it. I was very rough. I had a favorite boy… I married without love, so did he. It was our destiny, what can we do?”

From the marriage without love, Mrs. Yevgenya had three sons. After the birth of the second son, her husband left the family and went abroad. He returned 10 years later. The third son was born to save the family.

“There was no democracy then. He was my husband, my khozyain [master]. My Armen was born 11 years after his brothers. I no longer had my mother, I didn’t have a helper. I was working, my children were growing up by themselves. My oldest sons are disabled from the war: both were wounded. One of them went to Leningrad [St. Petersburg] and didn’t come back; the other is still in military service. After my husband’s death, my Armen and I were left together. Whatever you see in this house is my Armen’s doing. He didn’t get to enjoy it,” says the grandma, wiping the small door of the washing machine with a dry cloth. She does this after every wash — Armen gave her the washing machine as a gift — so it doesn’t become ruined all of a sudden.

She began participating in the war unofficially in 1988. She transported letters and messages. The Russian soldiers didn’t dare search her. In 1992, her two sons had already volunteered — at age 13–14. Her four brothers too.

Yevgenya’s medals. Medal for Courage for defending the Fatherland, demonstrating personal bravery, and performing service and civic duties in life-threatening conditions.

A view from Yevgenya’s apartment.

In 1992, during the Karabakh War, a twelve-person squad was formed, all of them women. Yevgenya was a sniper. In August 1993, during a military operation near old Kubatlu, Yevgenya was wounded, receiving injuries from her knees to her chest.

“Our squad was formed in 1992. We were 12 people, all of us women. In the squad, we had only one SVD [Dragunov sniper rifle]; the rest of us fired with automatic weapons. I was a sniper. We were at a military operation near old Kubatlu on August 23–24, 1993. That day we had one casualty and two injured from the girls. I was one of them,” describes the woman and lifts the skirt of her dress. There is a ragged line of stitches from above her knee to her chest.

“For three days we were at military operations and for three days, at home. I would come home, make something to eat, do the laundry. My children grew up by themselves… I didn’t close my eyes at night also during the war. Sometimes I would hug the injured, pressed them to me, make them comfortable, so their wounds wouldn’t hurt. I would spend the entire night sitting. What was I to do? I also had two soldiers in the war.”

The war robbed Mrs. Yevgenya of everything: the lives of the two brothers, the childhood her sons never had, her youth and beauty. It gave her two shrapnels cased in her old white body, two crutches under her arms, and one medal for courage.

Photographs by Nazik Armenakyan

Text by Sona Martirosyan

–

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is the longest war in the South Caucasus, with alternating phases of relative peace and escalation, including not only the Artsakh–Azerbaijan border, but also the administrative district of the Republic of Armenia. The negotiations underway through the OSCE Minsk Group since 1994 have yielded no tangible benefits to the societies of the two countries: The ceasefire agreement, in fact, is the only legal act in the last 23 years aimed at resolving the conflict. This is a war that already three generations have inherited.

Two hundred women, 42 of whom died on the battlefield, participated in the 1988–1994 Nagorno-Karabakh War. There is no clear information on women’s participation in the second, more intense stage of the Nagorno-Karabakh War, the Four-Day War in April 2016. But there is other data: The number of girls pursuing military education doubled after the conflict escalated in April, and more than 2,000 women serve in the Armed Forces of the Republic of Armenia.